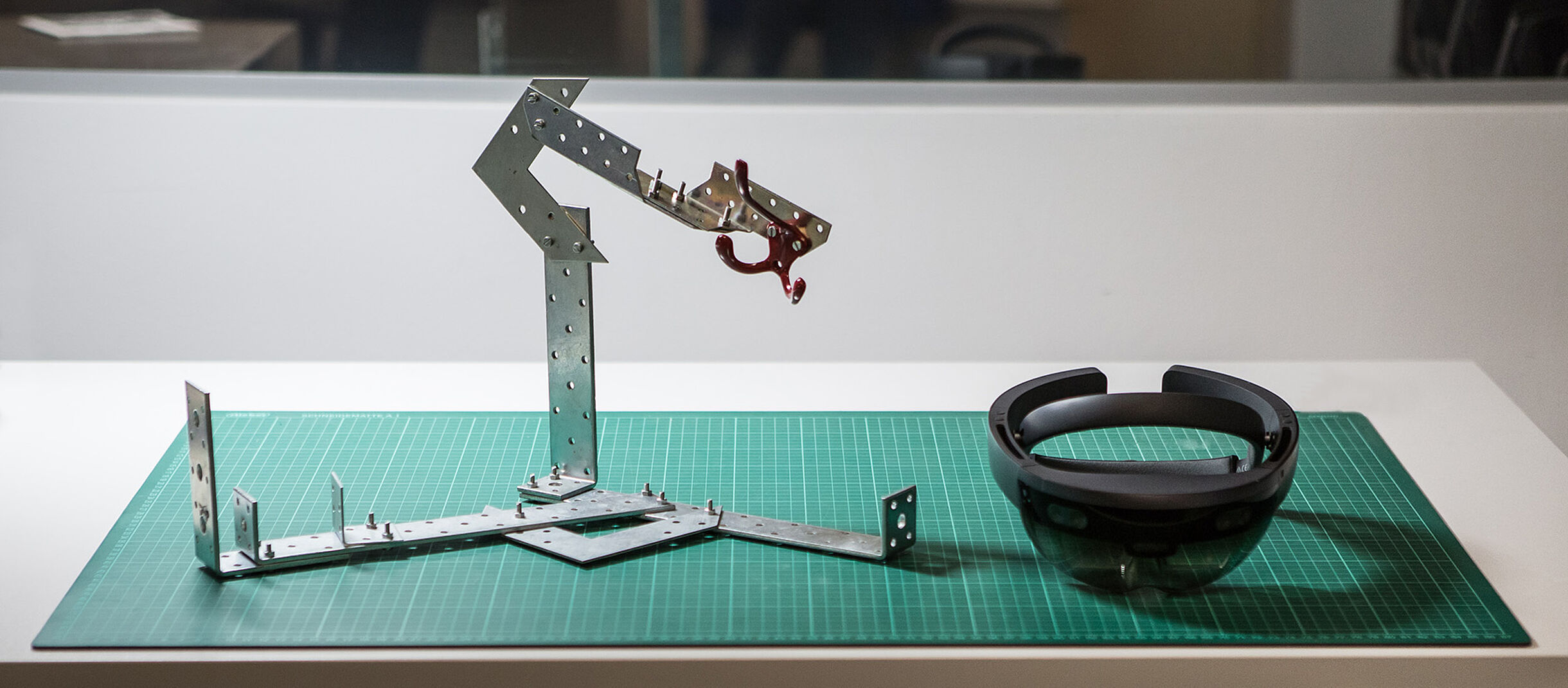

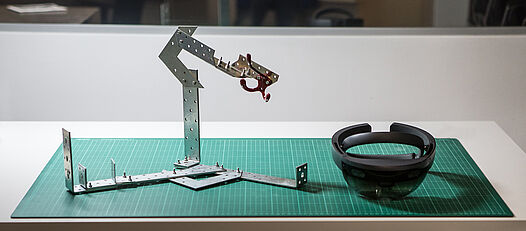

When using machines, people are often faced with complex tasks that they do not feel up to. Under the catchphrase "Deconstructing Complexity", user experience research at the AIT Austrian Institute of Technology is developing methods to make it easier for people to deal with technology - both in everyday life and when operating machines.